After the successful launch of the Mandala Art series last year by Parisian coin producer the Art Mint, it was quite obvious that the set would expand this year with another of these epic 3oz antique-finish coins. The first in the new annual series was called Mandala Art ‘Kalachakra’, and as you’d expect from the name, was a traditional representation of a Mandala. As it was described last year, a Mandala in its most basic form is a radially balanced pattern comprised of a square with a gate on each side, the whole containing a circle with a centre point. Meant to represent the universe, while the term is Sanskrit in origin, it is used by many religions and philosophies, especially Buddhism.

This years design has moved away from the Sanskrit origins and taken the idea of incorporating another style of art and fitting it into the basic definition of a mandala. The 2016 coin is adorned with an art style that has become hugely popular through mediums such as tattooing, and through a rising general interest in the period of history, Celtic Art. A particular favourite, the repeating patterns and symmetry present in Celtic Art, or at least modern interpretations of it, is a natural fit for something designed to inspire comparisons with original Sanskrit mandala’s. The 2015 coin had at its centre a clear Swarovski crystal, but this second entrant in the Mandala Art range has replaced that with a Malachite half-sphere, also perfectly centred on the reverse face and again, looking quite integrated into the design, something not always the case on coins so adorned.

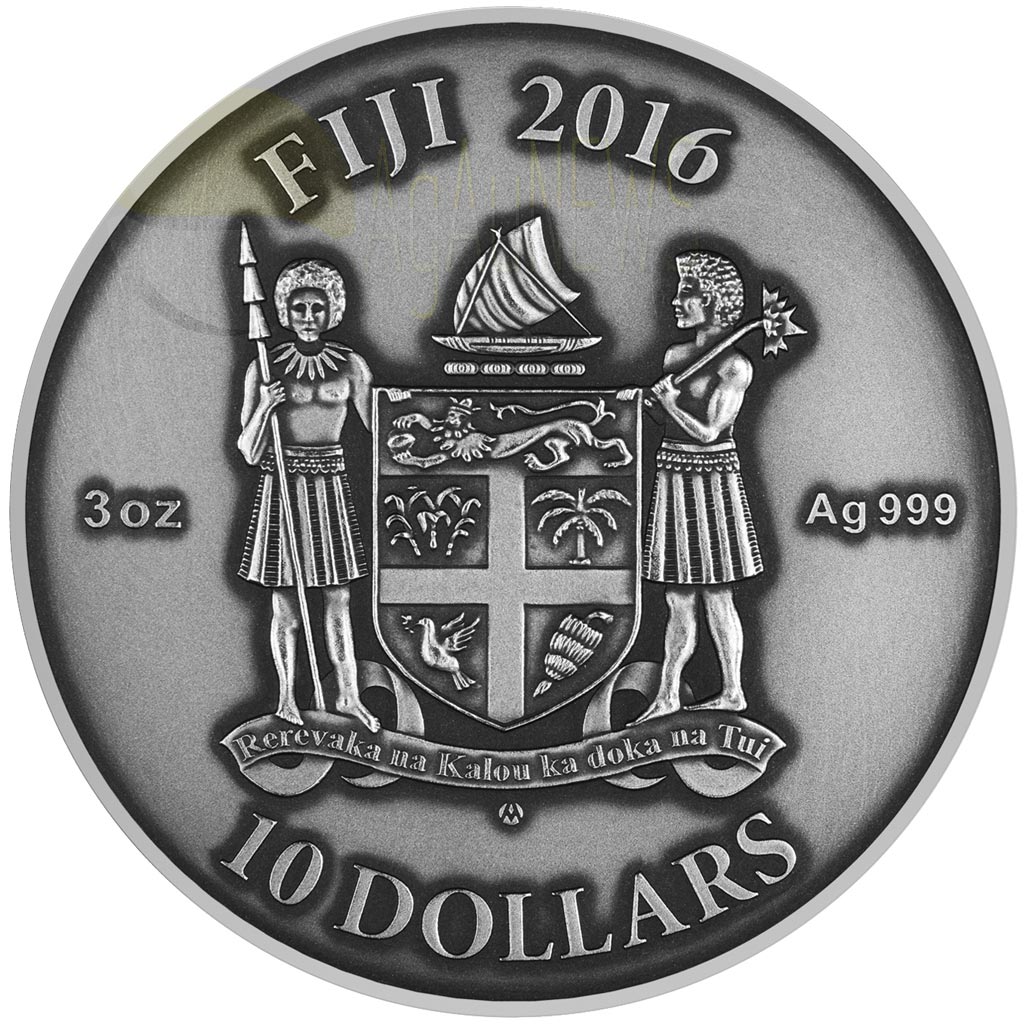

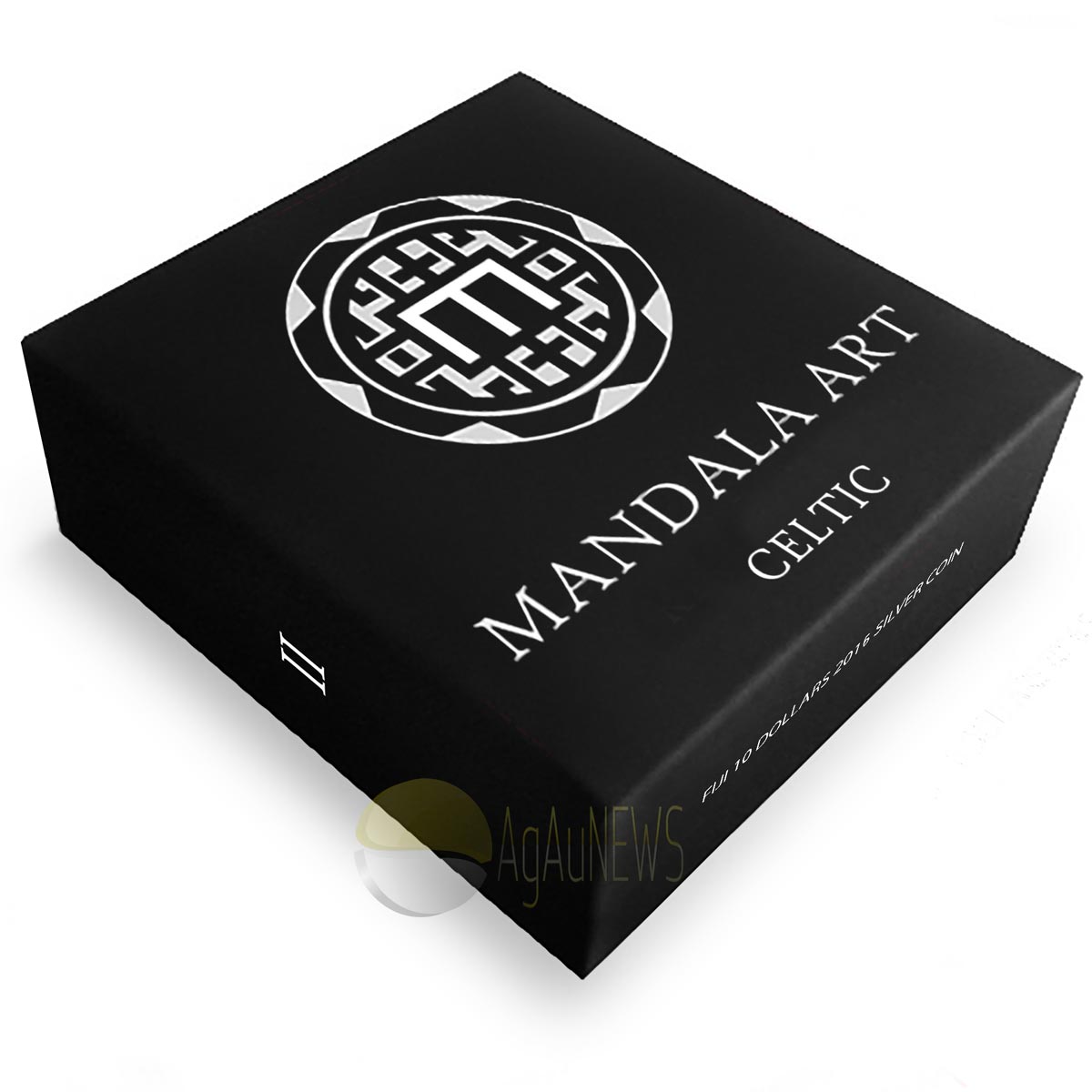

It’s again issued for the island state of Fiji and is still limited to just 500 pieces. The specification hasn’t changed, much of the extra weight of the coin going on thickness rather than diameter, something that allows the serial number to be etched on the edge. Rimless, high-relief, and hand-antiqued, this is clearly a higher-end release, and while similar in spec to the large selection of art-architectural coins on the market, a refreshing change of style from them. Supplied in a box with a certificate of authenticity, this Mandala coin starts to ship at the end of February, much earlier than last years July.

Like last years coin, this one is available directly from the Art Mint as well, and for a limited time (only a few days) is available with a very nice discount. These normally sell for around issue price, so it seems a good deal.

MINTS DESCRIPTION

What is a Mandala?

The meaning of mandala comes from Sanskrit meaning “circle.” It appears in the Rig Veda as the name of the sections of the work, but is also used in many other civilizations, religions and philosophies. Even though it may be dominated by squares or triangles, a mandala has a concentric structure. Mandalas offer balancing visual elements, symbolizing unity and harmony. The meanings of individual mandalas is usually different and unique to each mandala.

The mandala pattern is used in many traditions. In the Americas, Indians have created medicine wheels and sand mandalas. The circular Aztec calendar was both a timekeeping device and a religious expression of ancient Aztecs. In Asia, the Taoist “yin-yang” symbol represents opposition as well as interdependence. Tibetan mandalas are often highly intricate illustrations of religious significance that are used for meditation. From Buddhist stupas to Muslim mosques and Christian cathedrals, the principle of a structure built around a center is a common theme in architecture.

In common use, mandala has become a generic term for any diagram, chart or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically; a microcosm of the universe. Representing the universe itself, a mandala is both the microcosm and the macrocosm, and we are all part of its intricate design. The mandala is more than an image seen with our eyes; it is an actual moment in time. It can be can be used as a vehicle to explore art, science, religion and life itself.

Carl Jung said that a mandala symbolizes “a safe refuge of inner reconciliation and wholeness.” It is “a synthesis of distinctive elements in a unified scheme representing the basic nature of existence.”

CELTIC ART

The Celts were people in Iron Age and Medieval Europe who spoke Celtic languages and had cultural similarities, although the relationship between ethnic, linguistic and cultural factors in the Celtic world remains uncertain and controversial.

Celtic art is generally used by art historians to refer to art of the La Tène period across Europe, while the Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, that is what “Celtic art” evokes for much of the general public, is called Insular art in art history. Both styles absorbed considerable influences from non-Celtic sources, but retained a preference for geometrical decoration over figurative subjects, which are often extremely stylised when they do appear; narrative scenes only appear under outside influence. Energetic circular forms, triskeles and spirals are characteristic.

The interlace patterns that are often regarded as typical of “Celtic art” were in fact introduced to Insular art from the animal Style II of Germanic Migration Period art, though taken up with great skill and enthusiasm by Celtic artists in metalwork and illuminated manuscripts. Equally, the forms used for the finest Insular art were all adopted from the Roman world: Gospel books like the Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne, chalices like the Ardagh Chalice and Derrynaflan Chalice, andpenannular brooches like the Tara Brooch. These works are from the period of peak achievement of Insular art, which lasted from the 7th to the 9th centuries, before the Viking attacks sharply set back cultural life.

In contrast the less well known but often spectacular art of the richest earlier Continental Celts, before they were conquered by the Romans, often adopted elements of Roman, Greek and other “foreign” styles (and possibly used imported craftsmen) to decorate objects that were distinctively Celtic. After the Roman conquests, some Celtic elements remained in popular art, especially Ancient Roman pottery, of which Gaul was actually the largest producer, mostly in Italian styles, but also producing work in local taste, including figurines of deities and wares painted with animals and other subjects in highly formalised styles. Roman Britain also took more interest in enamel than most of the Empire, and its development of champlevé technique was probably important to the later Medieval art of the whole of Europe, of which the energy and freedom of Insular decoration was an important element. Rising nationalism brought Celtic revivals from the 19th century.

ADVERTISEMENTS

Leave A Comment