EVOLUTION OF LIFE (2015) by CIT Coin Invest

Back in 2007, the Liechtenstein-based coin producer Coin Invest Trust, issued a hit coin for the National Bank of Mongolia. The debut coin in a new series called Wildlife Protection, it went on to win the prestigious Coin of the Year award in 2010. That series went from strength to strength and every issue has been widely applauded for its quality and most importantly, its design. Sadly now ended, although Numiscollect are reimagining them in conjunction with CIT as fully dimensional coins, we were fortunate to see a spiritual successor debut in 2015.

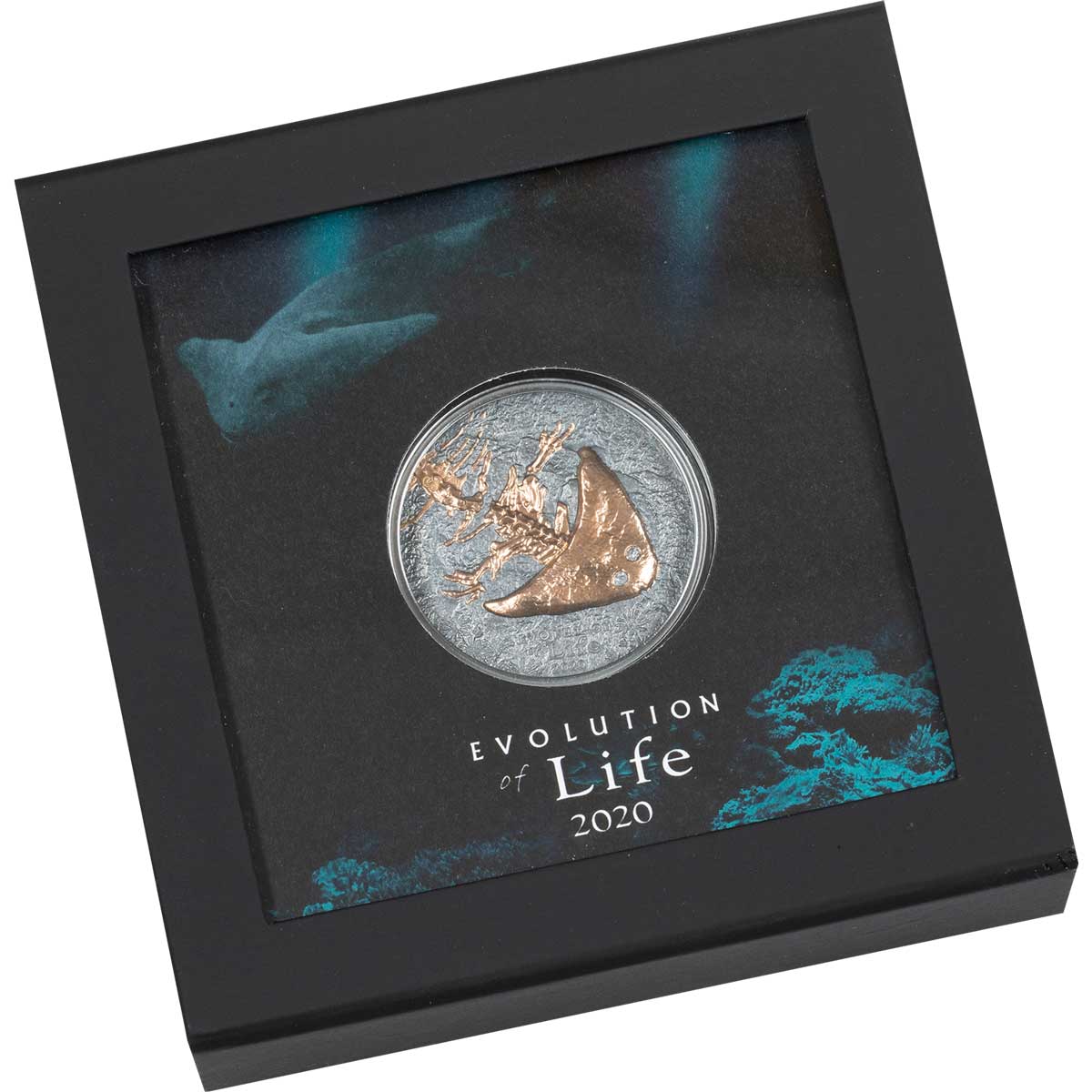

Evolution of Life widens out the pot of subjects from modern Mongolian fauna, to literally the prehistoric life of the whole planet. The beauty of this series lies in the way the creatures have been depicted – as fossils – and the how. An ounce in weight, these antique finished coins employ Smartminting to allow some impressive levels of high relief. The fossil depictions stand proud of the coin background, which is made to resemble rock, just as you’d expect to see if the fossil was in the process of being removed from the matrix.

The fossil itself is beautifully glded using copper-rich red gold, similar to that used to produce the Sovereign and the Krugerrand, which stands out splendidly against the dark hue of the antiquing. While there are quite a few inscriptions on the reverse face, almost all related to the coin title rather than the issue details, they’re remarkably innocuous and don’t distract from the end result at all. The obverse is the standard Mongolian one that CIT uses in several of its ranges.

As you’d expect with CIT, there’s a companion series of minigold 0.5 gram coins to sit alongside the main attraction. Despite this producers innovative range of shaped minigold issues, these ones are straightforward coins, not even using their cutting edge techniques to expand the diameter out to almost 14 mm. These remain strictly fixed at the standard 11 mm diameter. Despite the basic format, they do a great job reproducing the silver coin in spirit and remain nice coins in the minigold field. Unlike the silver coins, these come unboxed as standard, although a small and neat one is available as an option.

Outside of this, CIT have partnered with AllCollect to release the debut ammonite issue as a huge one-kilogram variant. It retains the design, but ramps it up to a huge 100 mm diameter. A gorgeous coin, but one that has yet to see a sequel. All of these coins are beautiful and amongst the best in their genre. Hopefully the series will go on as long as Wildlife Protection did. It’s already picking up awards in the same manner.

2015 Ammonoidea (Devonian)

First appearing in the Devonian period and descended from an animal called a Bactrite, Ammonites roamed the seas of the earth from around 400 million years ago, and didn’t die out until around 65mya, a staggering period given the relatively infinitessimal time mankind has been around. At every one of the world major extinction events only a few species of ammonites survived, but they always bounced back until their luck finally ran out, along with the dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous period.

Ammonites were predatory mollusks, very mobile and with tentacles. Very close in appearance to the still-living Nautilus, they were in fact more closely related to the octopi. Usually spiral in shape, although straight species aren’t rare, they remained buoyant using a siphuncle, basically a biological pump and siphon system. Each of the segments in the shell were a chamber that the animal resided in and the pattern of the edge of each chamber, called a a suture, is what marks out each species.

Many species probably carried ink sacs for defence, at least some were plankton feeders, and many were munched on by huge undersea reptiles called Mosasaurs. Fossils are plentiful and range from the tiny up to a colossal two meters in diameter! Some, especially in Europe, are so beautifully preserved that the original mother-of-pearl sheen is still fully intact. Others are less well preserved but show extraordinary internal detail with some having quite amazingly complex suture lines. Regardless, fossils are plentiful and make a great way to date rock formations.

2016 Trilobita (Ordovician)

Trilobites, meaning “three lobes”, are a fossil group of extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita and form one of the earliest known groups of arthropods. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the Atdabanian stage of the Early Cambrian period (521 million years ago), and they flourished throughout the lower Paleozoic era before beginning a drawn-out decline to extinction when, during the Devonian, all trilobite orders except the Proetids died out. Trilobites finally disappeared in the mass extinction at the end of the Permian about 250 million years ago. The trilobites were among the most successful of all early animals, roaming the oceans for over 270 million years. By the time trilobites first appeared in the fossil record, they were already highly diversified and geographically dispersed. Because trilobites had wide diversity and an easily fossilized exoskeleton, an extensive fossil record was left behind, with some 17,000 known species spanning Paleozoic time.

Trilobites had many lifestyles; some moved over the sea bed as predators, scavengers, or filter feeders, and some swam, feeding on plankton. Most lifestyles expected of modern marine arthropods are seen in trilobites, with the possible exception of parasitism. All trilobites are thought to have originated in present-day Siberia, with subsequent distribution and radiation from this location. Trilobites appear to have been exclusively marine organisms, since the fossilized remains of trilobites are always found in rocks containing fossils of other salt-water animals such as brachiopods, crinoids, and corals. Within the marine paleoenvironment, trilobites were found in a broad range from extremely shallow water to very deep water. Trilobites are found on all modern continents, and occupied every ancient ocean from which Paleozoic fossils have been collected. The remnants of trilobites can range from the preserved body to pieces of the exoskeleton, which it sheds in the process known as ecdysis. In addition, the tracks left behind by trilobites living on the sea floor are often preserved as trace fossils.

Trilobites range in length less than 3 millimetres to well over 30 centimetres, with an average size range of 3–10 cm. Supposedly the smallest species is Acanthopleurella stipulae with a maximum of 1.5 millimetres. The world’s largest known trilobite specimen, assigned to Isotelus rex of 72 cm, was found in 1998 by Canadian scientists in Ordovician rocks on the shores of Hudson Bay. (Source: Wikipedia)

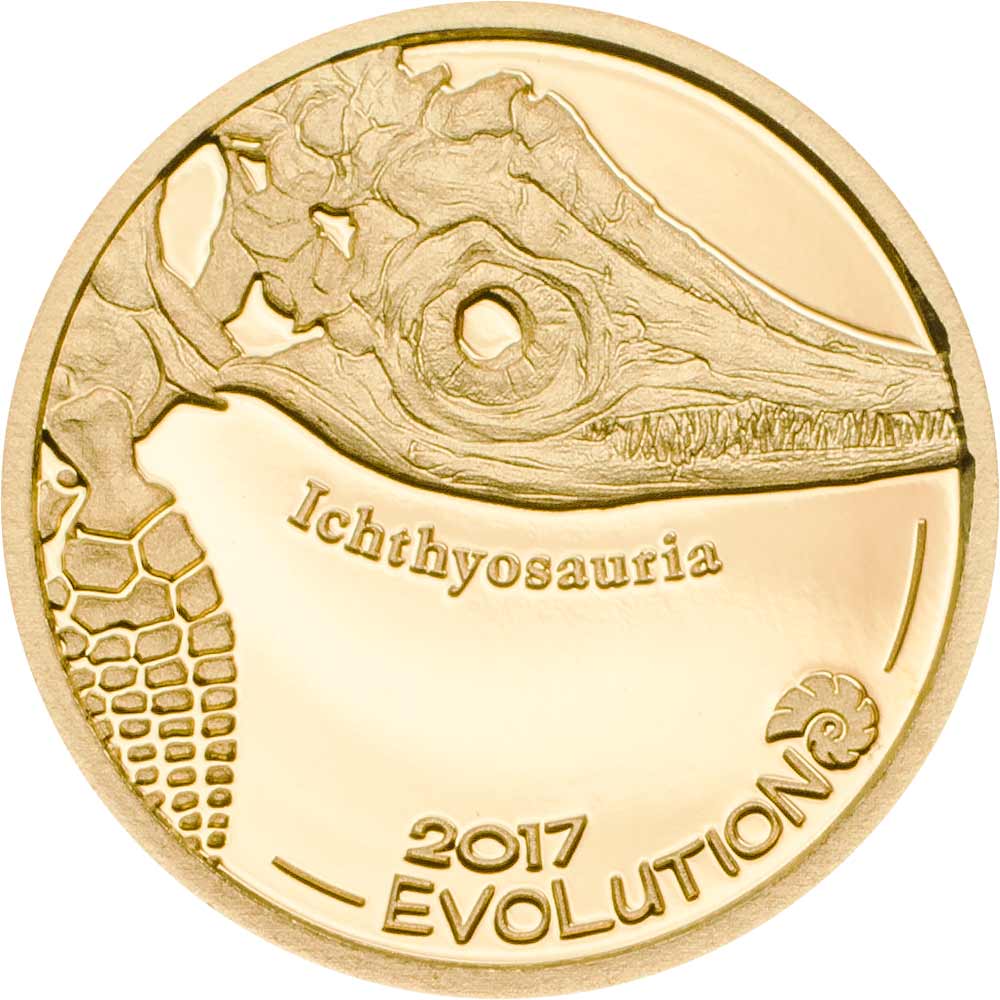

2017 Ichthyosauria (Triassic)

Ichthyosaurs (Greek for “fish lizard”) are large marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia (‘fish flippers’ – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1840).

Ichthyosaurs thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fossil evidence, they first appeared approximately 250 million years ago (mya) and at least one species survived until about 90 mya, into the Late Cretaceous. During the early Triassic Period, ichthyosaurs evolved from a group of unidentified land reptiles that returned to the sea, in a development parallel to that of the ancestors of modern-day dolphins and whales, which they gradually came to resemble in a case of convergent evolution. They were particularly abundant in the later Triassic and early Jurassic Period, until they were replaced as the top aquatic predators by another marine reptilian group, the Plesiosauria, in the later Jurassic and Cretaceous Period. In the Late Cretaceous, ichthyosaurs became extinct for unknown reasons.

Science became aware of the existence of ichthyosaurs during the early nineteenth century when the first complete skeletons were found in England. In 1834, the order Ichthyosauria was named. Later that century, many excellently preserved ichthyosaur fossils were discovered in Germany, including soft tissue remains. Since the late twentieth century, there has been a revived interest in the group leading to an increased number of named ichthyosaurs from all continents, over fifty valid genera being now known.

Ichthyosaur species varied from one to over sixteen metres in length. Ichthyosaurs resembled both modern fish and dolphins. Their limbs had been fully transformed into flippers, which sometimes contained a very large number of digits and phalanges. At least some species possessed a dorsal fin. Their heads were pointed, the jaws often equipped with conical teeth to catch smaller prey. Some species had larger bladed teeth to attack large animals. The eyes were very large, probably for deep diving. The neck was short and later species had a rather stiff trunk. These also had a more vertical tail fin, used for a powerful propulsive stroke. The vertebral column, made of simplified disc-like vertebrae, continued into the lower lobe of the tail fin. Ichthyosaurs were air-breathing, bore live young, and were probably warm-blooded. (Source: Wikipedia)

2018 Pterosauria (Cretaceous)

Pterosaurs (Greek pteron and sauros, meaning “wing lizard”) were flying reptiles thaty existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight. Their wings were formed by a membrane of skin, muscle, and other tissues stretching from the ankles to a dramatically lengthened fourth finger.

There were two major types of pterosaurs. Basal pterosaurs (also called ‘rhamphorhynchoids’) were smaller animals with fully toothed jaws and, typically, long tails. Their wide wing membranes probably included and connected the hind legs. On the ground, they would have had an awkward sprawling posture, but their joint anatomy and strong claws would have made them effective climbers, and they may have lived in trees. Basal pterosaurs were insectivores or predators on small vertebrates. Later pterosaurs (pterodactyloids) evolved many sizes, shapes, and lifestyles. Pterodactlyoids had narrower wings with free hind limbs, highly reduced tails, and long necks with large heads. On the ground, pterodactyloids walked well on all four limbs with an upright posture, standing plantigrade on the hind feet and folding the wing finger upward to walk on the three-fingered “hand.” They could take off from the ground, and fossil trackways show at least some species were able to run and wade or swim. Their jaws had horny beaks, and some groups lacked teeth. Some groups developed elaborate head crests with sexual dimorphism.

Pterosaurs sported coats of hair-like filaments known as pycnofibers, which covered their bodies and parts of their wings. Pycnofibers grew in several forms, from simple filaments to branching down feathers. These are homologous to the down feathers found on both avian and some non-avian dinosaurs, suggesting that early feathers evolved in the common ancestor of pterosaurs and dinosaurs, possibly as insulation. In life, pterosaurs would have had smooth or fluffy coats that did not resemble bird feathers. They were warm-blooded active animals. Pterosaurs spanned a wide range of adult sizes, from the very small anurognathids to the largest known flying creatures of all time, including Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx, which reached wingspans of at least nine metres. The combination of endothermy, a good oxygen supply and strong muscles allowed pterosaurs to be powerful and capable flyers.

Pterosaurs had a variety of lifestyles. Traditionally seen as fish-eaters, the group is now understood to have included hunters of land animals, insectivores, fruit eaters and even predators of other pterosaurs. They reproduced by means of eggs, some fossils of which have been discovered.(Source:Wikipedia)

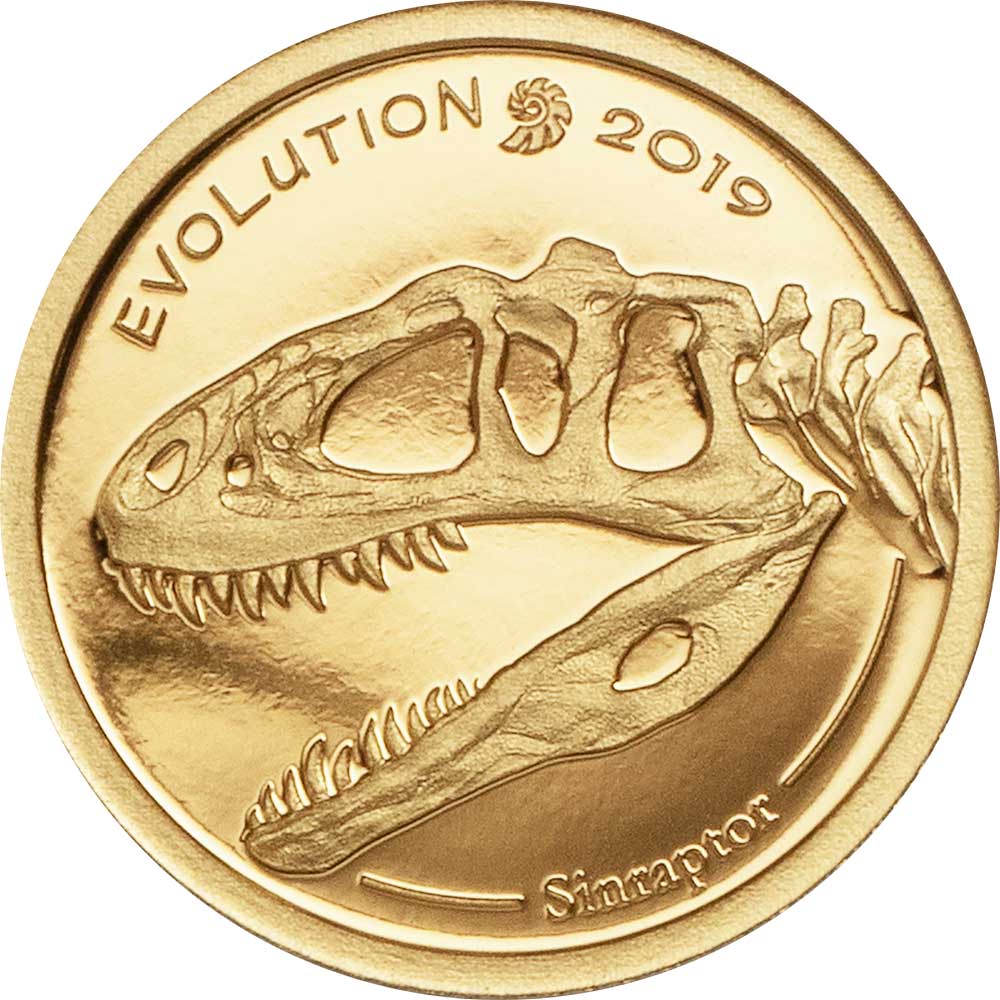

2019 Dinosauria (Jurassic)

Sinraptor is a theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic and the name Sinraptor comes from the Latin prefix “Sino”, meaning Chinese, and “raptor” meaning robber. Despite its name, Sinraptor is not related to dromaeosaurids (often nicknamed “raptors”) like Velociraptor. Instead, it was a carnosaur distantly related to Allosaurus. Sinraptor and its close relatives were among the earliest members of the Jurassic carnosaurian radiation. Sinraptor still remains the best-known member of the family Metriacanthosauridae, with some older sources even using the name “Sinraptoridae” for the family.

The holotype specimen of Sinraptor was uncovered from the Shishugou Formation during a joint Chinese/Canadian expedition to the northwestern Chinese desert in 1987, and described by Philip J. Currie and Zhao Xijin in 1994. Standing nearly 3 meters tall and measuring roughly 7.6 meters in length, two species of Sinraptor have been named. S. dongi, the type species, was described by Currie and Zhao in 1994. A second species, originally named Yangchuanosaurus hepingensis by Gao in 1992, may actually represent a second species of Sinraptor. Whether or not this is the case, Sinraptor and Yangchuanosaurus were close relatives, and are classified together in the family Metriacanthosauridae. Holtz estimated it to be 8.8 meters in length. In 2016 other authors stated that the holotype (IVPP 10600) was a subadult and estimated the size of the probable adult specimen (IVPP 15310) at 11.5 meters and 3.9 tonnes.

2020 Lepospondyli (Carboniferous)

Diplocaulus (meaning “double caul”) is by far the largest and best-known of the lepospondyls, an extinct genus of lepospondyl amphibians characterized by a distinctive boomerang-shaped skull. Remains attributed to Diplocaulus have been found from the Late Permian of Morocco and represent the youngest-known occurrence of a lepospondyl, although they ranged from the Late Carboniferous to Permian periods of North America and Africa. Much of modern knowledge on the genus is based on Diplocaulus magnicornis, as it outnumbers any other Diplocaulus remains by hundreds of specimens and had a wide temporal distribution throughout the red beds of Texas and Oklahoma.

Diplocaulus had a stocky, salamander-like body, but was relatively large, reaching up to 1 m in length. Although a complete tail is unknown for the genus, a nearly complete articulated skeleton described in 1917 preserved a row of tail vertebrae near the head. This was construed as circumstantial evidence for a long, thin tail capable of reaching the head if the animal was curled up. Most studies since this discovery have argued that anguiliform (eel-like) tail movement was the main force of locomotion utilized by Diplocaulus and its relatives.

The most distinctive features of this genus and its closest relatives were a pair of long protrusions or horns at the rear of the skull, giving the head a boomerang-like shape. A new hypothesis for the function of the horns was presented by South African paleontologist Arthur Cruickshank & fluid dynamicist B.W. Skews in a 1980 paper. They proposed that the tabular horns acted as a hydrofoil, allowing the animal to more easily control how water flows over its head. In the process of their investigation, Cruickshank & Skews developed a full-scale model of the head and a portion of the body of a Diplocaulus, constructed from balsa wood and modelling clay. The model was placed in a wind tunnel, and subjected to several tests which showed that the horns generated significant lift, allowing the animal to rise in the water column of a river or stream quite quickly and easily. (Wikipedia)

2021 Hominidae (Quaternary)

Paranthropus is a genus of extinct hominin which contains two widely accepted species: P. robustus and P. boisei. However, the validity of Paranthropus is contested, and it is sometimes considered to be synonymous with Australopithecus. They lived between approximately 2.6 and 0.6 million years ago (mya) from the end of the Pliocene to the Middle Pleistocene.

Paranthropus is characterised by robust skulls, with a prominent gorilla-like sagittal crest along the midline–which suggest strong chewing muscles–and broad, herbivorous teeth used for grinding. However, they likely preferred soft food over tough and hard food. Paranthropus species were generalist feeders, but P. robustus was likely an omnivore, whereas P. boisei was likely herbivorous and mainly ate bulbotubers. They were bipeds. Despite their robust heads, they had comparatively small bodies. Average weight and height are estimated to be 40 kg at 132 cm for P. robustus males, 50 kg at 137 cm for P. boisei males, 32 kg at 110 cm for P. robustus females, and 34 kg at 124 cm for P. boisei females.

They were possibly polygamous and patrilocal, but there are no modern analogues for australopithecine societies. They are associated with bone tools and contested as the earliest evidence of fire usage. They typically inhabited woodlands, and coexisted with some early human species, namely A. africanus, H. habilis, and H. erectus. They were preyed upon by the large carnivores of the time, specifically crocodiles, leopards, sabertoothed cats, and hyaenas. (Wikipedia)

2022 Synapsida (Permian)

Synapsids were the largest terrestrial vertebrates in the Permian period, 299 to 251 million years ago, with numbers and variety severely reduced by the Permian–Triassic extinction. They are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptiles and birds. The Synapsids group includes mammals and every animal more closely related to mammals than to sauropsids. When all non-avian dinosaurs were wiped out by the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, the mammalian synapsids diversified again to become the largest land and marine animals on Earth.

Edaphosaurus is a genus of extinct synapsids that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 303.4 to 272.5 million years ago, during the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian. It’s important as one of the earliest-known, large, herbivorous, four-legged land-living vertebrates. In addition to the large tooth plates in its jaws, the most characteristic feature of Edaphosaurus is a sail on its back. A number of other synapsids from the same time period also have tall dorsal sails, most famously the large apex predator Dimetrodon. Researchers have suggested that such sails could have provided camouflage, wind-powered sailing over water, anchoring for extra muscle support and rigidity for the backbone, protection against predator attacks, fat-storage areas, body-temperature control surfaces, or sexual display and species recognition.

The animal measured from 0.5 to 3.5 metres in length and weighed over 300 kg. Edward Drinker Cope named and described Edaphosaurus (“pavement lizard”) in 1882, based on a crushed skull and a left lower jaw from the Texas Red Beds. He noted in particular the “dense body of teeth” on both the upper and lower jaws, and used the term “dental pavement” in a table in his description.(Wikipedia)

2023 Nimravidae (Paleogene)

Nimravidae, an extinct family of prehistoric mammals, holds a fascinating place in the evolutionary history of carnivorous mammals. These creatures, commonly referred to as “false saber-toothed cats,” thrived from the Eocene to the Miocene epochs, spanning approximately 40 million years. Nimravids were not true cats but had evolved convergent features, such as elongated canines, resembling those of the famous saber-toothed cats like Smilodon.

Nimravids were diverse in size and appearance, ranging from small, agile hunters to larger, more robust forms. Their fossilized remains have been found across North America and Eurasia, shedding light on their evolutionary adaptations and ecological roles. These carnivores likely occupied niches as ambush predators, utilizing their impressive canine teeth to subdue prey efficiently.

However, the Nimravidae family eventually succumbed to competition with true cats, which had more advanced features and hunting strategies. Despite their eventual extinction, Nimravids provide a captivating glimpse into the complex web of prehistoric life and the ever-evolving nature of Earth’s fauna. Studying these intriguing creatures offers valuable insights into the dynamics of ancient ecosystems and the process of mammalian evolution.

This one is being handled by European producer AllCollect, but it’s a larger copy of the CIT-issued original. Nothing in the three years since the original issue has diminished this ammonite design. It’s a beautiful looking piece that we can only imagine will look exceptional at over thirty times the weight. With a diameter of 100 mm, every little piece of detail will be visible. The picture of the big and small coin together in the Gallery below is an approximated mock-up AgAuNEWS did to give an indication of just how much bigger the new beast is.

The obverse is also a straight copy, although with a larger denomination, of course. The packaging is simply a larger version of the light wood box with a themed lid that CIT useed for the 1oz coin.

Also distributed by AllCollect, it’s another stunning coin. Again, you can see in the image above, just how much bigger than the original one ounce issue the kilo coin really is.

SPECIFICATION

| EVOLUTION OF LIFE | |||

| DENOMINATION | 500 Togrog (Mongolia) | 20,000 Togrog (Mongolia)(AllCollect) | 1000 Togrog (Mongolia) |

| COMPOSITION | 0.999 silver | 0.999 silver | 0.9999 gold |

| WEIGHT | 31.1 grams | 1,000 grams | 0.5 grams |

| DIMENSIONS | 38.61 mm | 100.00 mm | 11.0 mm |

| FINISH | Antique | Antique | Proof |

| MODIFICATIONS | High relief, rose gilding | High relief, rose gilding | Some issues gilded |

| MINTAGE | 999 | 99 | 15,000 |

| BOX / C.O.A. | Yes / Yes | Yes / Yes | Optional / Yes |

Leave A Comment