Today is the centenary of the Armistice that ended the First World War. The Royal Mint remembers.

The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. A time that has resonated throughout popular conciousness over the last century and the time that the First World War, also called the Great War, came to an end. A brutal war the likes of which had never been seen before. The scale of slaughter and the relatively short period over which it took part, forever changed the reality of warfare. Killing became mechanised, and by the time the armistice came into force at 11 a.m. Paris time on 11 November 1918, highly efficient. Sadly, the armistice would also sow the seeds of an even greater conflict just 20 years later.

The Royal Mint has run a comprehensive World War One centenary program starting in 2014 and ending here, with the release of their final six-coin set. These sets have been real highlights of the numismatic remembrance around the world. Eschewing any form of gimmickry, they have carried classic designs, and this last set is no exception. Designed by five different Royal Mint artists, the six coins concentrate on the legacy of the war and not the battles, men and equipment that marked it. Each carries an edge inscription (click image to see it for each coin).

This is a beautiful set. The Peace coin and the Imperial War Museums coins in particular, are very nicely done, but all get their point across eloquently. The obverse is common to all and features the Jody Clark effigy of Queen Elizabeth II. Each coin is struck in a standard ounce of sterling silver to a proof finish. They come presented in a fine quality box and just 600 of these £465.00 sets will be struck. Available now, it’s a shame there’s no donation to the Poppy Appeal by the mint, but outside of that, a solid recommendation for the remembrance of a date that must never be forgotten.

MINTS DESCRIPTION

As the journey from outbreak to Armistice draws to a close, The Royal Mint brings their story of war to a close with the release of the final six-coin set. Designed by David Lawrence, David Cornell, Edwina Ellis, John Bergdahl and David Rowlands each coin tells its own story but together they honour the sacrifices made and captures the hope for peace.

Unique to this final set, five of the coins are finished with edge inscriptions by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy, taken from a poem specially commissioned by The Royal Mint. The Dove of Peace coin brings the commemoration to a close with an inscription symbolising the Armistice.

Nicola Howell, The Royal Mint’s Director of Consumer Business said: “In 2014 The Royal Mint began a five-year programme to commemorate every year of the First World War. As the journey to Armistice nears, we are proud to honour those who lost their lives during the war and the pursuit for peace with the final six-coin set.”

THE DOVE OF PEACE: When the war came to an end on 11 November 1918, it did not mean instantaneous peace. Countries faced the political turmoil that resulted from the war. On 18 January 1919, the Paris Peace Conference began and the conference led to five major peace treaties.

The Dove of Peace is David Lawrence’s second design. David depicts the traditional dover of peace finally flying about the barbed wire of war. David said, “It is a great honour to be part of the programme of commemoration. In researching these coins, I looked at many images of the conflict, in all its diverse aspects. It was a humbling experience: glimpsing, from my peaceful, comfortable world, a time of great fear and desperation.

There have been big ceremonies in the past few years, but sacrifice, grief and remembrance are very small personal things, quiet reflections in a quiet moment; long-term things that echo down the generations.”

THE WREATH OF REMEMBRANCE: As the formalities of the peace settlement were negotiated into 1919, finding ways to honour those who lost their lives during the war became a preoccupation. Ordinary objects became an instant reminder of loved ones from photographs to letters.

Communities gathered around stone monuments to remember the war dead. However, purchasing a poppy to fundraise for wounded servicemen became the most common was to mark commemoration.

After two minutes of silence occurred on 11 November, Remembrance Sunday was adopted as a day which everyone gathered to pay tribute to those who served at war and a wreath of poppies was laid to remember the war dead.

Designed by sculptor, artist and illustrator David Lawrence, David said “The Armistice was of course the moment of cessation of hostilities. I used the typeface by MacDonald Gill, as I feel the war graves are very noble, a well-kept tribute and form of remembrance. You see the stark white among the green, you stand back and see tens of thousands ranked, all those people. Every single one had someone. People’s memories didn’t end on that day, the Armistice simply began a time when people could start to remember.”

WAR MEMORIALS: As the world attempted to come to terms with the loss of loved ones during the war, the need for a focal point of national mourning became apparent. This was noticed and in London a temporary structure made of wood and plaster designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, in the form of a cenotaph stood.

The cenotaph attracted more than a million people, who left behind 100,000 wreaths over a period of four days. The year later the temporary cenotaph was replaced with a permanent structure made from Portland stone.

Experienced coinage artist John Bergdahl said “When I began working on this series I remember reading the inscription on the Cenotaph at Whitehall, ‘The glorious dead’. Looking back at these devastating battles you can’t help but feel that there is nothing glorious about war.”

“When I turned to the Armistice, I wanted to create something formal, and in the end I opted to show the Cenotaph itself. It is a formal, solemn piece of architecture that simply speaks for itself. When we think of remembrance, it is where our thoughts turn.”

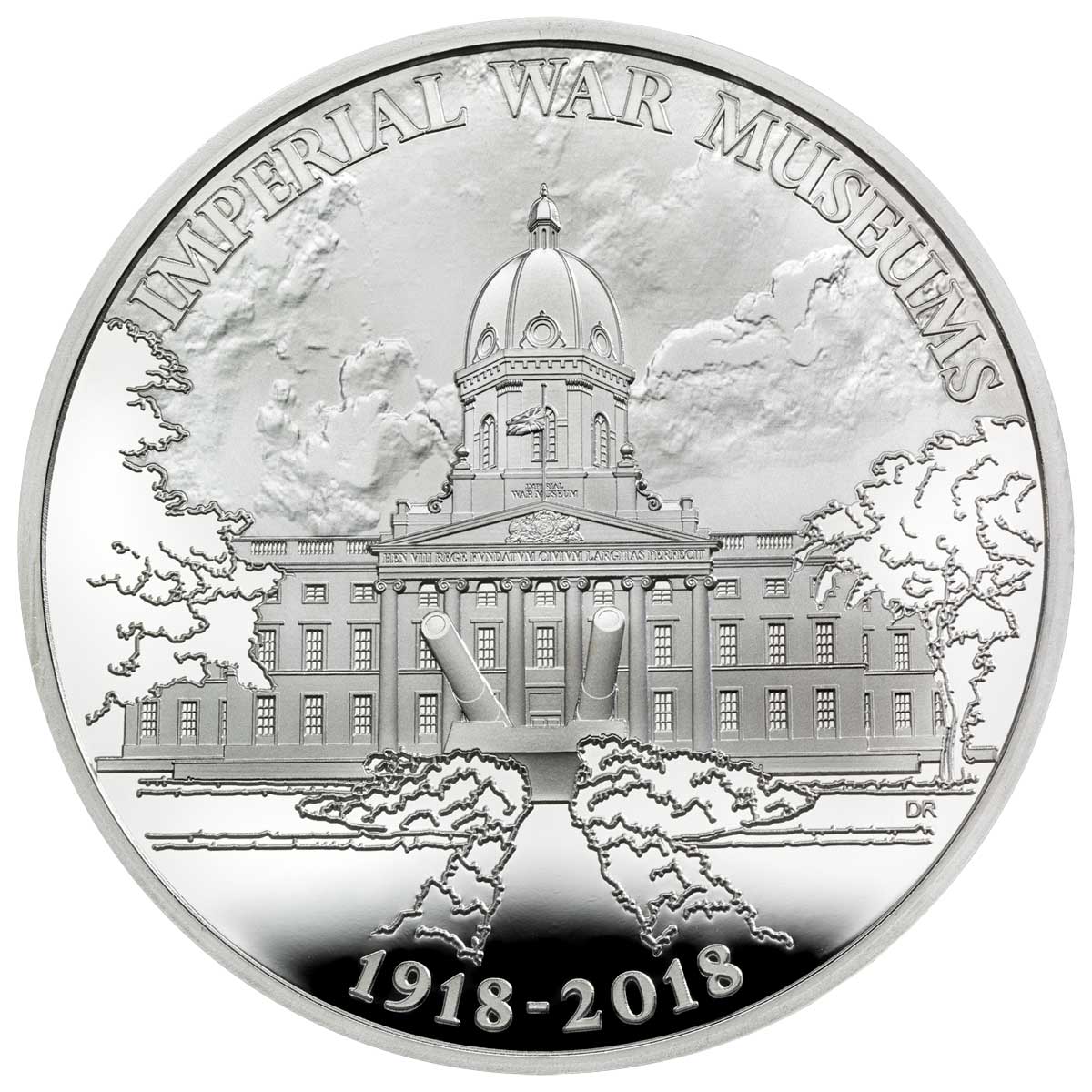

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUMS: The Imperial War Museum was founded on 5 March 1917 when the War Cabinet approved a proposal by Sir Alfred Mond MP for the creation of a national war museum to record the events still taking place during the Great War.

Today, the Imperial War Museum is a leading authority on conflict and its impact, focusing on Britain, its former Empire and the Commonwealth, from First World War to the present.

Military artist David Rowlands said, “The Imperial War Museum in London was set up before the end of the war, with the intention of collecting items from battlefields, among other things, like photographs and so on, so that the war could be experienced to a certain extent in a physical form.

“Most visitors to the museum would have been touched by the war – they would have lost friends and relatives, or had loved ones wounded in action – and this would give them a physical experience of what those close to them had been through. It struck me that this was the only way to do that in those days. There was no television, of course, and the men who returned spoke little of what they had endured. The Imperial War Museum in London for me was not just a museum, it was really trying to convey a message, and preserve memories.”

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES: The history of the Commonwealth War Graves began in the First World War. The Imperial War Graves Commission was established to bury and commemorate the dead and the missing.

Sculptor David Cornell honours the Imperial War Grave commission with his design. David said, “My design shows the cross of sacrifice with the inverted sword which represents the faith of the majority of the dead. The cross is surrounded by graves of the unknown warriors of many different faiths and beliefs. I wanted the design to be emotive and portray the same feelings I get when I see the graves of so many thousands of unknown soldiers.”

POPPIES: The poppy became a symbol associated with remembrance of the First World War when it flourished in the soil churned up by artillery fire.

Artist Edwina Ellis said of her inspiration behind the design “Wild poppies and cornflowers germinate in disturbed soil and they are pioneers – the tragic metaphor of their burgeoning in the battlefields was not lost on fighting troops. These wildflowers can be seen in photographs of trenches and were often described, most memorably by Robert Graves.

“There were small trench gardens tended by troops, especially by Germans, and it is good to feel there is a symbol for all those fallen that does not dissemble. I wanted a real, wild poppy on the design to symbolise the exact poppies those fighting men saw, tended, or watched grow over their mates’ makeshift graves.”

| SPECIFICATION | |

| DENOMINATION | £5 United Kingdom |

| COMPOSITION | 0.925 silver |

| WEIGHT | 31.107 grams |

| DIMENSIONS | 38.61 mm |

| FINISH | Proof |

| MODIFICATIONS | Edge inscription |

| MINTAGE | 600 |

| BOX / COA | Yes / Yes |

Leave A Comment