Canada week continues with a couple of personal favourites. Like the British Royal Mint, the Royal Canadian Mint does history coins very well and coins like these are often overlooked in the clamour for information on the flashy or high-profile licensed designs. These two in particular are superb examples of the genre and while celebrating events from two seperate wars, both look to the sea for inspiration.

First up is a really excellent Merchant Navy design full of action and quite exquisitely done. Perspective, often a problem with ship art, is bang on the mark, the sea and bomb splash look realistic, and the detail is quite sublime. The George IV obverse is a nice change from the usual effigy of Queen Elizabeth II as well. All round a great coin happily devoid of colour or gilding. As a two-ounce fine silver coin it’s the pricier of the two coins here, selling for $169.95 CAD.

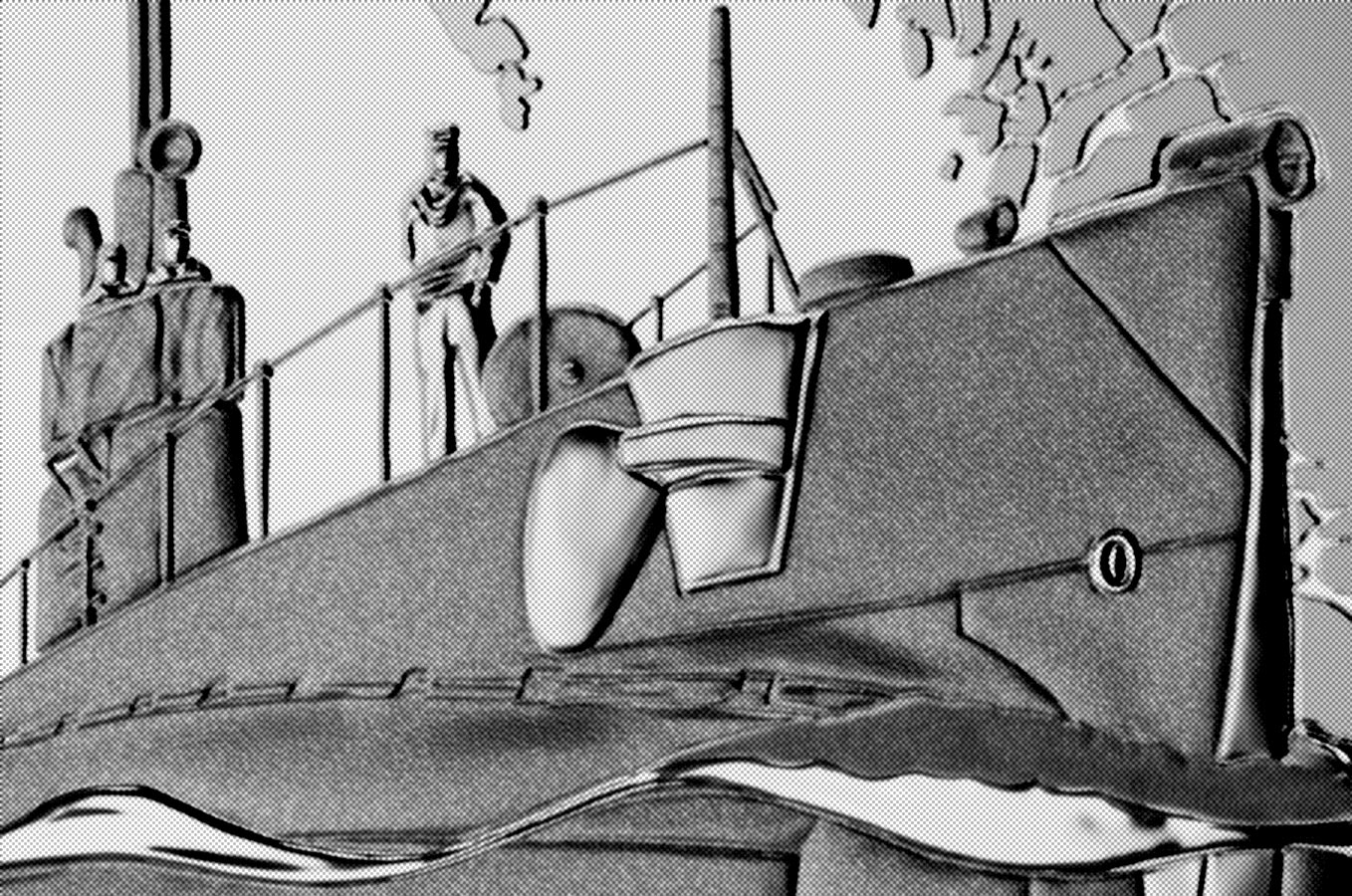

The second coin is equally superb and also by Yves Bérubé. Again, the sense of perspective is just perfect and the design very clean, well-struck and of a fascinating subject, early submarines. The outline of Canada’s Pacific coastline is nicely integrated into the scene without spoiling it. The obverse is also a historical one, in this case the effigy of King George V. At just one-ounce in weight, this coin is obviously cheaper, coming in at $89.95 CAD.

Both are available now and listed inexplicably on the RCM website as for sale in the US and Canada only, something that has gone from applying to licensed properties only, to just about everything on the site.

CANADA’S MERCHANT NAVY: BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC

MINTS DESCRIPTION

The reverse design by Canadian artist Yves Bérubé features an impeccable combination of expert engraving and beautiful finishes and depicts the dangerous conditions endured by transatlantic ships during the Battle of the Atlantic between 1939 and 1945. It is a calm evening on July 11, 1943; in the foreground, the ocean steamer SS Duchess of York (left) is featured prominently, with a thick plume of steam billowing out from its funnels. Requisitioned as a troopship during the war, the large vessel is part of the convoy dubbed “Faith,” which has been spotted by enemy aircraft off the coast of Spain.

Two Focke-Wulf Fw-200 Kondors have begun their high-level bombardment, with one bomb hitting the water starboard side off the ship’s bow, where detailed engraving adds movement through the motion of the water’s surface. One of the convoy’s escort ships, the Tribal-class destroyer HMCS Iroquois (right), has unleashed anti-aircraft fire but it is all in vain against this airborne attack. While SS Duchess of York and 34 of its crew would be added to the Allied casualties suffered during the Second World War’s Battle of the Atlantic, 628 of its survivors would be rescued and transported to safety by Iroquois.

| DENOMINATION | COMPOSITION | WEIGHT | DIAMETER | FINISH | MINTAGE | BOX / COA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $30 CANADIAN | 0.9999 SILVER | 62.27 g | 54.00 mm | PROOF | 5,000 | YES / YES |

ADVERTISEMENTS

CANADIAN HOME FRONT: FIRST SUBMARINES

MINTS DESCRIPTION

The reverse design by Yves Bérubé highlights the importance of the addition of two submarines to the Royal Canadian Navy’s fleet in August of 1914. The CC Class submarine is prominently featured in the centre of the image, its hull pointed forward towards the viewer as though emerging from the image. The vessel’s keel and diving planes can be seen below the surface of the water; above, a sailor stands on the deck in front of the conning tower as he surveys the horizon. In the background to the right of the submarine, a beautifully detailed map of British Columbia’s coastline looms large; this added element provides geographical context to the story of Canada’s first submarines, which were used to patrol the coastline depicted here.

| DENOMINATION | COMPOSITION | WEIGHT | DIAMETER | FINISH | MINTAGE | BOX / COA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $20 CANADIAN | 0.9999 SILVER | 31.39 g | 38.00 mm | PROOF | 7,500 | YES / YES |

Leave A Comment